Ghost nets:

The silent killer haunting our oceans

For over 20 years, OceanEarth Foundation’s, Ghostnets Australia program has been at the forefront of ghost net mitigation efforts – from grassroots initiatives to global alliances, reflecting a commitment to change and adaptation. Each year we edge a little closer to our vision of an ocean free from ghost nets.

Over that time we have:

- prevented over 14,000 abandoned, discarded or lost fishing nets from continuing their deadly journey around the ocean, where they trap and further threaten our endangered marine life by removing them from this system.

- rescued more than 400 marine turtles from a slow and painful death.

- discovered where the nets are coming from and the reasons why this sudden increase is occurring in our region.

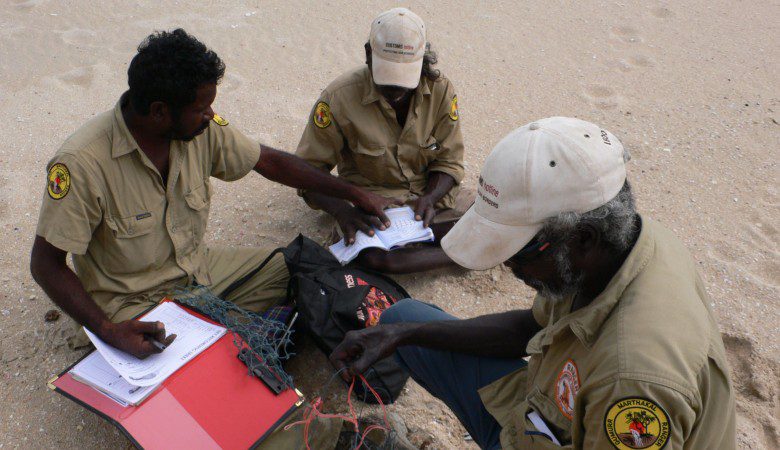

- supported Indigenous rangers from 40 different clan groups to continue their stewardship of their customary lands and adjacent marine environments by providing local Indigenous rangers with the much-needed resources, training in data collection and building their skills in effective decision-making and communication.

- found a creative re-use for the piles of rubbish that has evolved into a new genre of art, resulting in purchases by prestigious art collectors, museums and galleries globally, and

- worked to stop the issue at the source and find sustainable disposal solutions to this complex issue.

GhostNets Australia is powered by communities, and like these communities, we are continuously evolving.

- No ghost gear from international sources washing up in northern Australia by 2030

- No ghost gear related to recreational fishing in Australia by 2030

- A circular program for end-of-life fishing gear within the commercial sector (fishing and aquaculture) by 2030

Want to get involved? Sign up to our newsletter to stay abreast of future opportunities.

What are ghost nets?

Our oceans face a silent threat: ghost nets. These abandoned, lost or discarded fishing nets (ALDFG – collectively known as ghost nets or ghost gear) are devastating marine life by indiscriminately trapping, entangling, and drowning countless species including marine mammals, seabirds and sea turtles. It is the deadliest form of marine plastic debris and in some places represents over 50% of all marine debris. Every year, it is estimated that between 500,000 and 1 million tonnes of fishing gear gets left in the ocean. Latest research equates this to nearly 2% of all fishing gear, comprising 2,963 km2 of gillnets, 75,049 km2 of purse seine nets, 218 km2 of trawl nets, 739,583 km of longline mainlines, and more than 25 million pots and traps are lost to the ocean annually.

Northern Australia is a global hotspot for ghost nets, particularly the remote Gulf of Carpentaria, where ghost nets continue to wreak havoc on ocean life. The Gulf is one of the last remaining safe havens for endangered marine and coastal species, including six of the world’s seven marine turtle species, dugongs, sharks and sawfish. Sadly, turtles account for around 80% of marine life caught in nets.

Despite concerted efforts over many years by Indigenous Rangers to rescue entrapped animals and the remove nets from our beaches and sea, they keep coming. In fact, the latest research shows that the number of ghostnets is increasing.

We need to stop this at the source – and this requires understanding where these nets come from.

The Young Man and The Ghost Net

Where do ghost nets come from and which fisheries are responsible?

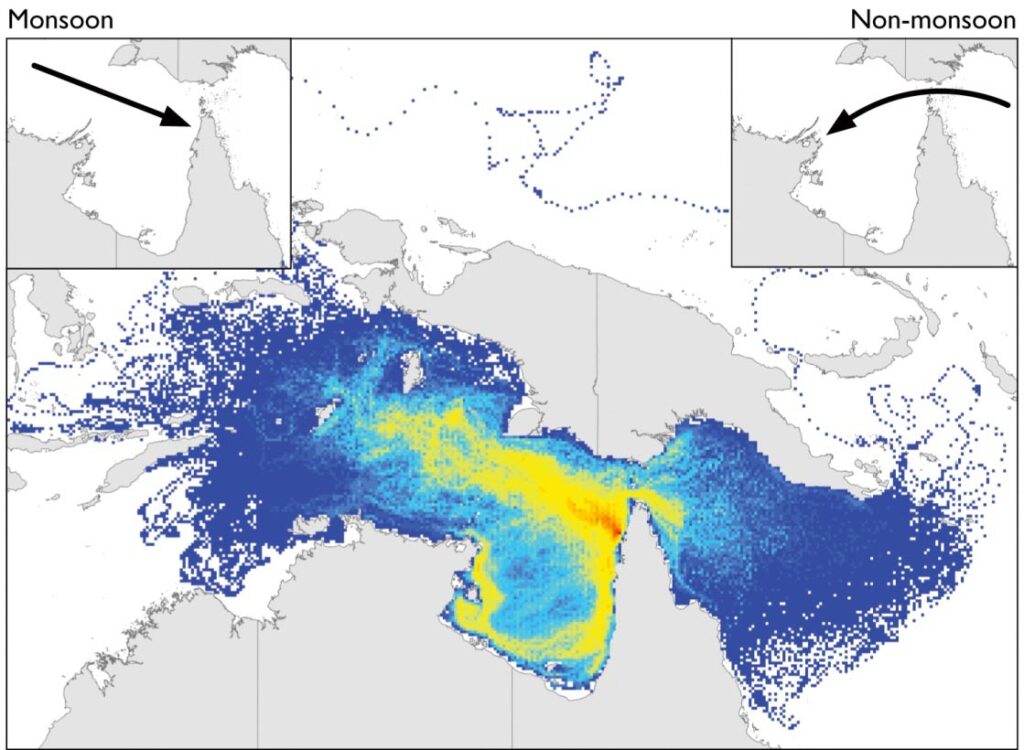

The data collected over 10 years by Indigenous Rangers through OceanEarth Foundation’s GhostNets Australia program revealed that more than 90% of ghost nets washing up across northern Australia originate from overseas. From our latest analysis in 2023 we know that the most frequent type of net is from trawl fisheries (42%), followed by gillnets (34%) and the rest mostly undetermined. We also now know, from work we did with CSIRO, that most of the nets originate from the Arafura Sea – a very important fishing area for Indonesia. The Arafura Sea is rich in nutrients, making it a prime fishing ground that attracts a vast range of activity, from the subsistence fisher to extremely large fishing vessels. For many years it supported high levels of illegal fishing activity until 2015 when the former Indonesia Fisheries Minister banned all foreign vessels and trawl vessels fishing in the area. The causes of gear loss/abandonment are complex and involve overcapacity leading to crowding and gear conflicts.

Ghost Nets Australia developed the Ghost Net Identification Guide in 2014 by working with Indigenous rangers over 10 years. Tens of thousands of net data and samples were contributed to the information in the guide, which has built upon the original WWF Net Kit first published in 2002.

Our Actions: What are we doing about ghost nets?

For over 20 years, we have been at the forefront of ghost net mitigation efforts – from grassroots initiatives to global alliances, reflecting a commitment to change and adaptation. Each year we edge a little closer to our vision of an ocean free from ghost nets.

Ghost Nets Australia began as a regional clean up and capacity building program in Northern Australia in 2004. In its early days Indigenous Rangers rescued of over 400 entangled turtles and removed over 14,000 nets from our beaches and estuaries working closely with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander coastal communities. Our experience led us to seek answers to some critical questions:

- Why do some regions receive more nets than others?

- How long does a ghost net stay in the water before it is beached?

- If these ghostnets aren’t Australian, where are they coming from?

- Who is responsible?

- How does a ghost net move?

- How many animals are entangled by a ghost net? and

- What can we do with all this rubbish?

We worked with research scientists and the Australian Government to answer these critical questions, leading to some important reports and research papers and building the knowledge base that we now rely on.

With this knowledge, in 2015 we began working at the international level to drive regional policy change and collaborative action to stop ghost gear at the source. This started with working with Indonesian fishers and the Government of Indonesia to understand the reasons that people lose nets. From this, our SeaNet Indonesia project worked with coastal communities in the Arafura Sea to strengthen sustainability and livelihoods while also reducing the discarding of nets. This included the first fishing net recovery project in Indonesia using a community cooperative model – the community collected 18 tonnes over 15 months.

OceanEarth Foundation is currently working with partners in Indonesia to scale this program, building on the lessons learned and utilising more localised/ in situ options for net recycling. This will go a long way towards helping achieve our 2030 of goal of no ghostnets coming to northern Australia .

In Australia we are partnering with OzFish to develop and implement a national plan of action to address ghostgear and litter from recreational fishing focused on fostering stewardship, product and packaging design, circularity through recycling.

How do we clean up ghost nets – finding sustainable disposal solutions?

The Indigenous Ranger groups across northern Australia continue to clean up the hundreds of ghostnets washing up every year – it is a huge burden.

We envisage an ocean free from ghost nets. While we are working hard to stop them at the source internationally, we are also developing solutions for what do we do with the tonnes of ghost nets that are washing ashore annually.

The safe and environmentally-sound disposal of rubbish in remote areas of Australia is extremely challenging; currently some ghost nets are burnt in situ while others are taken to local landfill – neither is appropriate.

In 2021 OceanEarth Foundation lead the GhostNets Needs Analysis and Feasibility Study for Northern Australia in collaboration with SMaRT @ UNSW (Sustainable Materials Research and Technology) to explore solutions for recycling or the sustainable disposal of ghostnets. As the nets are primarily plastic, we are working with recyclers to investigate viable solutions for re-manufacturing and creating new products from the collected nets; this would create increased economic outcomes for Indigenous communities across northern Australia. There are many recycling options in Australia and internationally, but for Northern Australia there are additional challenges including:

- Vast distances and limited access to some clean up locations

- Transportation costs are high and ghost nets can be 6km long and weight over 10 tonnes

- After exposure to the elements the plastic is contaminated and breaks down, turning into microplastics

- It can be difficult to identify the plastic type once the ghost net is degraded

- There is not a steady or predictable supply of ghost nets, like there is for household recycling, which makes planning difficult for recyclers.

What are the impacts of ghost nets on marine wildlife?

Ghost nets are deadly. This is not surprising given they are designed to catch fish and this will happen whether or not someone is attached to the end of them.

Research partnerships with CSIRO, University of Queensland and Indigenous Ranger groups have helped us shed light on the biodiversity impacts of ghost nets across northern Australia and more broadly.

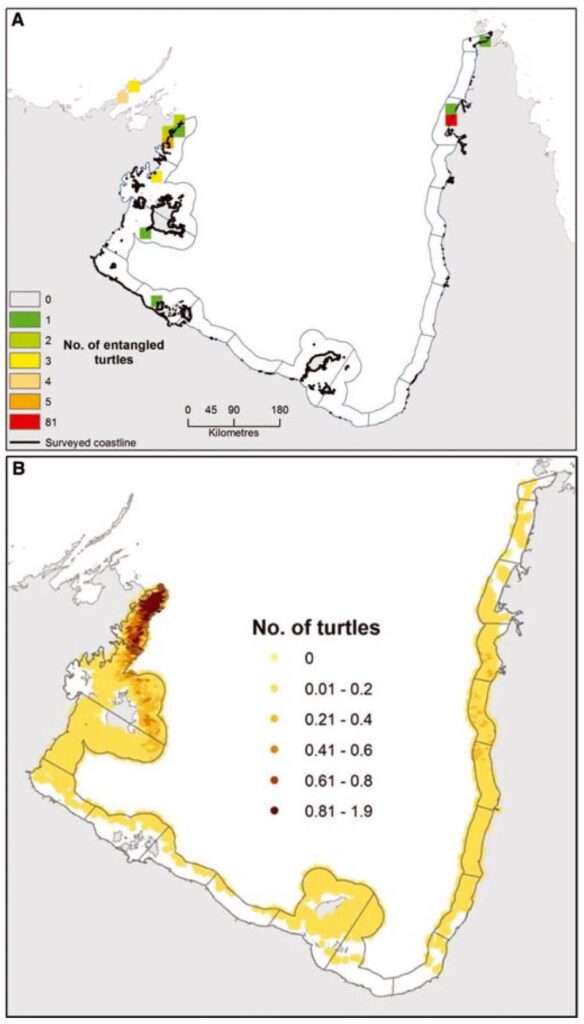

Through integrated analysis and field studies, we have been able to identify high-risk areas for turtle entanglement in the Gulf of Carpentaria; to determine the decay rate (half-life) of by-catch (the incidental capture of non-target species), particularly turtles and sharks in a ghost net suspended in the ocean; and an evaluation of which are the deadliest nets.

These findings have been crucial in understanding the impact that ghost nets have on marine wildlife.

Ghostnets with relatively larger mesh and smaller twine sizes (e.g., pelagic drift nets which are a type of gillnet) have the highest probability of entanglement for marine turtles. Catch rates for fine-mesh gill nets can be as high as 4 turtles/100 m of net length. From 8,690 ghostnets sampled we estimated the number of turtles caught was between 4866 and 14,600, assuming nets drift for 1 year. This is an alarming estimate and all the more reason why the countries in the Arafura region need to work together to stop the issue at the source to reduce this transboundary impact on marine wildlife in the region.

Read more about the research undertaken

Ghost nets are not just impacting on our wildlife though, they also create navigation hazards, can cripple vessels through propeller entanglement and cause loss of life and economic impacts.

Influencing Change: A Collective Endeavor to the ghost net issue

Advocacy and collaboration are critical to our mission of freeing the ocean of ghost nets. Through workshops, conferences, and partnerships, we advocate for government policy changes and industry reforms that not only clean up our coastlines and find appropriate recycling solutions for ghost nets but also prevent them entering the ocean in the first place.

OceanEarth Foundation has been working with the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) since inception to amplify our impact, unite global efforts to combat ghost gear and protect our oceans. As part of a global team, we work with GGGI to develop international policy, provide advice and key resources, including the Best Practice Framework for the Management of Fishing Gear .

In Australia, we have achieved some important outcomes over the years, with the first in 2004, and subsequently in 2018, where we held a pivotal role in shaping the Threat Abatement Plan for the impacts of marine debris on the vertebrate wildlife of Australia’s coasts and oceans (2018) under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. This process assisted the Australian Government Ghost Nets Initiative and has facilitated the ongoing clean-up of ghost gear and other marine debris, working towards sustainable disposal solutions. We continue to work with the Australian Government, through their Ghost Nets Initiative, towards achieving our goal of stopping ghostgear at the source.

Ghost nets continue to cast a shadow over our oceans, threatening marine life and coastal ecosystems. Yet, through collective action, innovation, and advocacy, we forge a path towards a sustainable future. Through our GhostNets Australia program we remain steadfast in our commitment to safeguarding our seas, guided by the wisdom of saltwater people and the promise of a cleaner, safer ocean for generations to come.

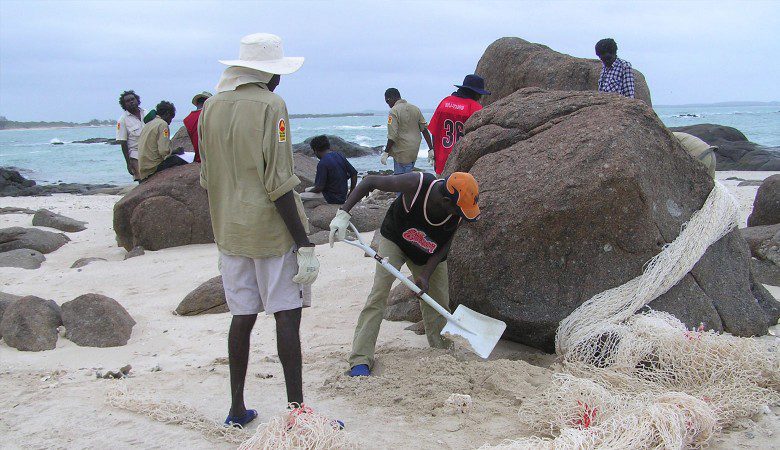

Indigenous Rangers: Ghost net guardians of the Coast

Indigenous rangers play a pivotal role in ghost net clean-up efforts and they face an enormous task the coastline is vast and remote with ghost nets varying in size from a football to a large truck. Some nets have even been measured at 6 kms long. Removing them from our shores is hard work, often requiring machinery to dig them out of the sand. The nets that remain at sea can pose an even bigger challenge as some are too large to move beyond the coastal fringe and require considerable work (including help from fishers and government agencies) to lift them from the ocean.

The ranger groups often require support to help them tackle large nets, including manpower, heavy equipment, resourcing and logistics. Some of our major clean-ups have only been possible through our strong partnerships, brute force and sheer persistence! As well as ghost nets, Indigenous rangers are also spending time and resources cleaning up marine plastic debris.

Between 2004 and 2015, our Ghostnets Australia program helped build the capacity of 40 coastal Indigenous communities to protect over 3,000 km of saltwater country from ghost nets and, despite the challenges posed by nets of varying sizes, their dedication remains unwavering. Empowering these communities with resources and training amplifies their impact and fosters a collective commitment to marine conservation. We are proud of the work we have undertaken to build the capacity of these Indigenous ranger groups to manage the ghost net issues. We’ve done this by supporting them with a ‘fee for service’ arrangement (2004-2013) which has ensured they are adequately funded to do this hard work. This support has also included supplying much needed resources such as vehicles, net cutters and extra manpower where required and helping them negotiate partnerships with many commercial entities such as mining companies or fishing charters.

The Gulf of Carpentaria has globally significant nesting and foraging grounds for six of the world’s marine turtles. Unfortunately, it is also one of the world’s ‘hot spots’ for ghost nets. This results in many turtles, (80% of wildlife found), becoming entangled in the nets and in most cases dying as a result. The rangers, during their beach patrols, attempt to rescue and in some cases rehabilitate as many as they can.

The GhostNets Needs Analysis and Feasibility Study for Northern Australia that we developed in collaboration with SMaRT @ UNSW (Sustainable Materials Research and Technology) details the specific challenges that Indigenous rangers face in their clean-up activities. This helped the Australian Government direct new funding to Indigenous ranger groups, including funding five new dedicated marine debris coordinators and a new vessel to transport vehicles and rangers to remote locations.

We continue to support the rangers to protect marine life through our ghost net identification work and the use of our Ghost Net ID guide. We are soon to update and improve our Ghost Net ID guide to cover the many new types of nets that are being found in the Gulf of Carpentaria

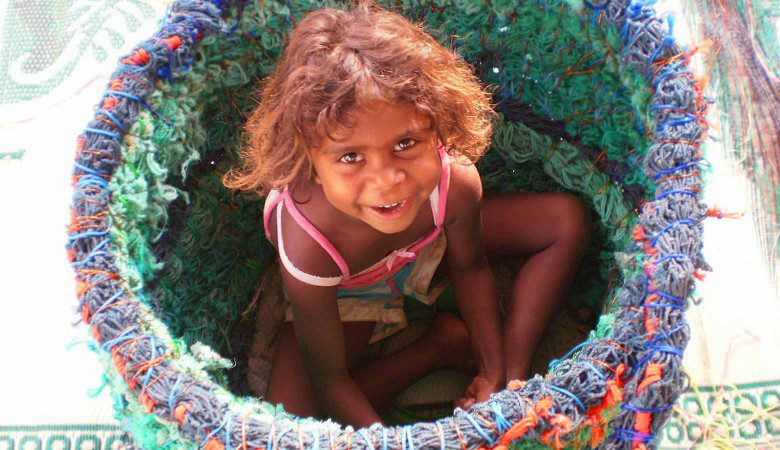

Ghost Net Art: Transforming Trash into Treasure

Ghost net art is a powerful vehicle for raising awareness about the damage that ghost nets inflict on the marine environment. With creativity, Indigenous communities have shown us how to transform discarded nets into breathtaking artworks, weaving stories of resilience and conservation.

Even before we began working with Indigenous rangers in northern Australia, people were repurposing ghost nets in diverse ways: as screens on verandahs, adorned with shells and glass or plastic floats; or fencing for chickens. Fishing and yam bags were made from pieces of ghost net found washed up on local beaches.

One place you wouldn’t find ghost nets though, was on display in museums and art galleries. But things have changed.

Our Ghost Net Art Director, Sue Ryan created the Ghost Net Art Project in 2009 from the conundrum of what to do with the mountains of ghost nets and other marine debris that Indigenous rangers were retrieving from beaches along Australia’s remote northern coastline.

The Ghost Net Art Project focuses on working with communities in ‘ghost net hotspots’ across northern Australia, sponsoring workshops with a view to engaging community members to create art and craft. Since the early days, ghost net art has featured in exhibitions around Australia, and important state and national and now international institutions have acquired many major pieces for their collections. Many communities across northern Australia are now involved in ghostnet art, creating beautiful pieces.

Ghost net art workshops

Fibre artists facilitating workshops in remote communities were key to encouraging local artisans to see ghost nets as a valuable material to work with. Over the years, we have sponsored more than thirty ghost net art workshops from remote Darnley Island in the Torres Straits to South Goulburn Island in the Arafura Sea. Most recently we have run workshops in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu with local artists.

Interested in running a Ghostnet Art workshop or getting involved – please get in touch.

The first ghost net art workshop with Erub/ Darnley Island:

Aurukun: One of the first Ghost Net Art workshops we ran.